I am almost finished with Chapter Two on my book about the Mascot, so I am working on my next one – could be Chapter Six, perhaps? Decided I am going to go non-linear on this. This is a brief outline on what I am researching and writing. I will most likely incorporate some of this into my lecture.

In Antebellum times, according to Jack Williams, carrying a personal grievance into a court of law debauched a gentleman’s character in polite society. Dueling remained a satisfactory proxy to the legal system. Newspaper editors were particularly under threat. An English traveler to America observed that editors were always practicing their gun skills so they could be ready when they were inevitably called upon. While some wrote what they wanted, others cloaked their opinions in a veil of politeness to avoid any possible challenges. After the Civil War, however, duels began to lose their appeal, as a “citizen who had fought his way through four years of devastating fratricidal warfare had little concern about being called a coward.” Yet the need to defend one’s good name still remained. In the latter 19th century, where 40 years earlier an insult or dispute would require strict adherence to the dueling code, it now lost its structure and rigidity and instead took a more “Wild West” turn where class structure and formality were cast aside and men spontaneously took their battles to the streets.

I am studying three specific cases that involve employees of the Mascot, and three murders that were results of what was written in its columns. They show that men who believed they were “slandered” demanded justice first in a hybrid-dueling fashion befitting to the time period. Yet, while dueling and death now inescapably warranted legal action, the New Orleans judicial system, in taking one step toward progress in prosecuting those involved, still held on to Antebellum beliefs, as evidence by the relatively light or nonexistent punishment for those who murdered or attempted to murder for the sake of their good name.

CASE #1

One of the Mascot’s weekly columns was Bridget Magee’s Society Notes, which featured “Bridget,” an Irish woman who wrote in a heavy Irish dialect and poked fun at the city’s politicians and social elite. In January of 1885 “she” wrote about Judge William T. Houston of the Civil District Court. In the column, Bridget referred to him as an “autocrat” and “would- be satrap,” and hinted at an immoral relationship with Dora Wallace, the daughter of a well-known former lawyer. Houston’s brother James who was the state tax-collector, set out to horsewhip the Mascot editors. Houston brought along ex-sheriff Robert Brewster who was then the state Registrar of Voters. One of the editors, George Osmond, and engraver Adolphe Zenneck were in the office when Houston and Brewster entered; Houston began beating Osmond with a club and then shot him in the hand. Injured, Osmond pulled a gun out of his desk, shot the gun out of Houston’s hands and turned his attention to Brewster who was firing on an unarmed Zenneck. Osmond shot Brewster multiple times. Houston and Brewster fled the offices, and Brewster subsequently died from his wounds the next day. It was later discovered that Houston and Brewster unloaded their entire chambers against the Mascot men. Osmond and Zenneck were both arrested for murder, although Osmond frequently testified that Zenneck did not even have a gun. The New York Times called Brewster’s funeral a “brilliant pageant” which was a “who’s who” of New Orleans society. Houston was acquitted of attempted murder and Osmond and Zenneck were later acquitted of Brewster’s murder, but would both be killed in a little over two years.

CASE #2

Zenneck became editor and part proprietor of the Mascot. In August of 1887, a 22-year-old machinist and amateur boxer named Dan Brown stormed the offices seeking revenge over something in “Mrs. Mulcahey’s Contributions,” a gossip column that “wrote” letters to Bridget Magee. The column insinuated that Brown was having an affair with his married landlord. Brown pushed Zenneck to the head of the stairs, fired two shots, and then ran to the street and fired two more in a crowd of about 50 people. Zenneck died of gunshot wounds to the leg. Brown was found guilty of manslaughter but with a strong recommendation from the jury for “mercy at the hands of the judge.” Brown was sentenced to six months in jail. Two weeks later, however, Governor McEnery (a frequent victim of the Mascot’s “truth seeking”) granted Brown a pardon and he was released. The Daily Picayune noted that it needed to be remembered that Brown had been “injuriously slandered” by the Mascot. Ironically, in May of 1882 the Mascot ran a cover story chiding McEnery for being the “pardoning governor” and a “grievous disappointment.”

CASE #3

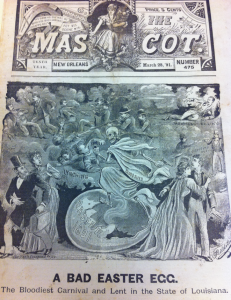

The Mascot declared early 1891 as “The Bloodiest Carnival and Lent in the State of Louisiana,” from the October 1890 murder of Police Chief David C. Hennessy, which led to the prison lynchings of eleven Italians accused of killing Hennessy, to the murder of a famous madam’s brother in her brothel, an assassination at the Market Place, a butcher murdering a pregnant married woman, and the death of Mascot reporter Frank Waters in a gun battle with former Police Captain Arthur Dunn on the corner of Canal and Bourbon Street.  In 1886, Waters killed Dunn’s friend Joseph Baker, the state assessor, in another gunfight in the street. Waters, who at the time was a reporter for the Daily Item, had written an article claiming that drunken policeman badgered “respectable citizens” at the voting polls. Enraged, Baker confronted him on the street, waving the news article in his face and eventually his pistol. Waters returned gunfire and shot Baker in the groin, a wound that would kill him the next day. Waters stood trial for murder, but was acquitted on the grounds that he acted in self-defense. Dunn never forgave Waters for the death of his friend and openly threatened him for years. On March 18, 1891 after a night of heavy drinking, Waters ran into Dunn on the street. This time Waters shot first. Dunn whirled around and the two men exchanged fire, advancing toward each other. Both men were wounded, and Waters died of his injuries in the carriage on the way to the hospital. Dunn was charged with murder and placed under a $10,000 bond, which was paid by Alex and John Brewster, the brothers of the deceased Robert Brewster who was killed by former Mascot editor George Osmond [I FIND THIS FASCINATING!]. Dunn was later acquitted of all charges.

In 1886, Waters killed Dunn’s friend Joseph Baker, the state assessor, in another gunfight in the street. Waters, who at the time was a reporter for the Daily Item, had written an article claiming that drunken policeman badgered “respectable citizens” at the voting polls. Enraged, Baker confronted him on the street, waving the news article in his face and eventually his pistol. Waters returned gunfire and shot Baker in the groin, a wound that would kill him the next day. Waters stood trial for murder, but was acquitted on the grounds that he acted in self-defense. Dunn never forgave Waters for the death of his friend and openly threatened him for years. On March 18, 1891 after a night of heavy drinking, Waters ran into Dunn on the street. This time Waters shot first. Dunn whirled around and the two men exchanged fire, advancing toward each other. Both men were wounded, and Waters died of his injuries in the carriage on the way to the hospital. Dunn was charged with murder and placed under a $10,000 bond, which was paid by Alex and John Brewster, the brothers of the deceased Robert Brewster who was killed by former Mascot editor George Osmond [I FIND THIS FASCINATING!]. Dunn was later acquitted of all charges.

The legal system slowly transformed the allure and acceptance of being victorious on the battlefield to being victorious in the courtroom. Men who once needed only a weapon and a space of ground measured off to restore their good name, now relied on a judge and jury. Yet, while New Orleanians supported the liberty of the press (philosophically and financially as the Mascot had the largest circulation of any illustrated journal in the South), they were also sympathetic to those who killed to defend any perceived injustice against those who operated under this very freedom.

Of course, many many many more details and theories in the chapter. Lots to do!