Everyone is familiar with a duel. After an altercation occurs and virtue is disputed, two men meet on a field, draw weapons, measure off their predetermined paces, aim and fire (or slash each other, depending on the weapon of choice).

In 19th century America, dueling was as ritualized as communion or confession. Duels were the panacea to dubious honor. When once fought with rapiers, swords, or sabers, a nick or slight wound was often adequate to preserve honor. But with the widespread availability of firepower, the Second Amendment was quite often interpreted as not only the right to bear arms, but the right to bear a grudge that typically ended in one, or both men, seriously wounded or dead.

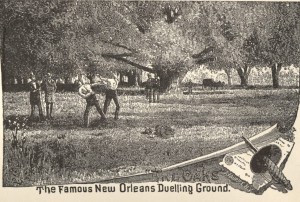

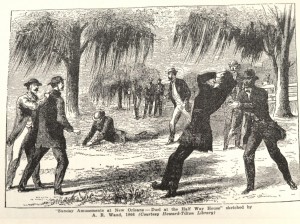

Many scholars claim that more duels were fought in New Orleans than in any other American city. One of the most popular spots to physically reinstate a man’s character through violence was a place in City Park under oak trees that became know as the Duelling Oaks. Historians declare that for a span of ten years in the mid 1830s to 1840s hardly a day went by when there wasn’t a duel fought under these magnificent trees. It was also during this time that an anti-dueling society was formed with many prominent citizens as members. New laws and ordinances outlawing duels were passed to support the public sentiment. Yet, dueling remained. Supreme Court justices dueled poetry professors, editors dueled each other over headlines, and men vying over the same lady at a ball often danced their last dance before heading out on the field with rancor and their weapon of choice.

In the 1880s in New Orleans, the time period where my research on the newspaper the Mascot begins, dueling was slowly (and stubbornly) becoming antiquated. Duels, and the men who fought them, were symbols of an epoch in New Orleans’ history when a man’s morality and merits were determined by his willingness to face death and his ability with the instrument he brandished. Men of this time period straddled the shift from old customs where a dispute could be settled with first drawn blood to the “civilized” nature of the court system. Often, they utilized both measures to win their battles.

Why am I bringing this up? Because I discovered that the men of the Mascot did both. A duel was fought based on the Mascot’s first libel suit (filed against them a mere two months into publication) just as they were about to head into court, and both arenas of combat saw interesting outcomes. But as I waded through injunctions, depositions, and affidavits, I wondered if that like the law, duels also followed a precise body of protocol. Certainly, newspapers alluded to such a thing, by stating that both men “followed the code,” but what exactly was this code? It’s contradictory that something so base and primal was dictated by a formal Victorian-style code. And as always, with any drastic contradiction comes intrigue.

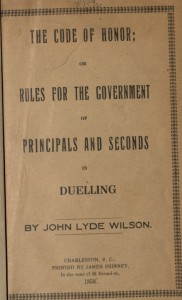

After some research, I discovered many articles and newspapers mentioning the Code Duello, or “Code of Honor,” but I could never find the actual document or a list of rules. Luckily, I found the book “The Code Of Honor: or Rules for the Government of Principals and Seconds in Duelling” by John Lyde Wilson, at the Williams Research Center and later at the Special Collections Department at Tulane where I was able to scan a copy of the 1858 book.

So if you are ever curious to know not only the rules of dueling, but the obligations for seconds (and you thought maids of honor had it bad), here you go. Among other things, you will learn what to do when insulted in public vs. at a wine table; how to deliver a note challenging a foe to duel and what it needs to say; what the usual distance is for dueling; and who needs to be on the grounds during a duel.

The man who adds in any way to the sum of human happiness is strictly in discharge of a moral duty – John Lyde Wilson.

RULES

For

Principal and Seconds in Duelling.

CHAPTER 1.

The Person Insulted, Before Challenge Sent

- Whenever you believe that you are insulted, if the insult be in public and by words or behavior, never resent it there, if you have self-command enough to avoid noticing it. If resented there, you offer an indignity to the company, which you should not.

- If the insult be by blows or any personal indignity, it may be resented at the moment, for the insult to the company did not originate with you. But although resented at the moment, you are bound still to have satisfaction, and must therefore make the demand.

- When you believe yourself aggrieved, be silent on the subject, speak to no one about the matter, and see your friend, who is to act for you, as soon as possible.

- Never send a challenge in the first instance, for that precludes all negotiations. Let your note be in the language of a gentleman, and let the subject matter of complaint be truly and fairly set forth, cautiously avoiding attributing to the adverse party any improper motive.

- When your second is in full possession of the facts, leave the whole matter to his judgment, and avoid any consultation with him unless he seeks it. He has the custody of your honor, and by obeying him you cannot be compromitted.

- Let the time of demand upon your adversary after the insult, be as short as possible, for he has the right to double that time in replying to you, unless you give him some good reason for your delay. Each party is entitled to reasonable time, to make the necessary domestic arrangements, by will or otherwise, before fighting.

- To a written communication you are entitled to a written reply, and it is the business of your friend to require it.

Second’s Duty Before Challenge Sent

- Whenever you are applied to by a friend to act as his second, before you agree to do so, state distinctly to your principal that you will be governed only by your own judgment,- that he will not be consulted after you are in full possession of the facts, unless it becomes necessary to make or accept the amende honorable, or send a challenge. You are supposed to be cool and collected, are your friend’s feelings are more or less irritated.

- Use every effort to soothe and tranquilize your principal; do not see things in the same aggravated light in which he views them; extenuate the conduct of his adversary whenever you see clearly an opportunity to do so, without doing violence to your friend’s irritated mind. Endeavor to persuade him that there must have been some misunderstanding in the matter. Check him if he uses opprobrious epithet towards his adversary, and never permit improper or insulting words in the note you carry.

- To the note you carry in writing to the party complained of, you are entitled to a written answer, which will be directed to your principal and will be delivered to you by his adversary’s friend. If this be not written in the style of a gentleman, refuse to receive it, and assign your reason for such a refusal. If there be a question made as to the character of the note, require the second presenting it to you, who considers it respectful, to endorse upon it these words: “I consider the note of my friend respectful, and would not have been the bearer of it, if I believed otherwise.”

- If the party called on, refuses to receive the note you bear, you are entitled to demand a reason for such refusal. If he refuses to give you any reason, and persists in such refusal, he treats, not only your friend, but yourself, with indignity, and you must then make yourself the actor, by sending a respectful note, requiring a proper explanation of the course he has pursued towards you and your friend; and if he still adheres to his determination, you are to challenge or post him.

- If the person to whom you deliver the note of your friend, declines meeting him on the ground of inequality, you are bound to tender yourself in his stead, by a note directed to him from yourself; and if he refuses to meet you, you are to post him.

- In all cases of the substitution of the second for the principal, the seconds should interpose and adjust the matter, if the party substituting avows he does not make the quarrel of his principal his own. The true reason for substitution is the supposed insult of imputing to you the like inequality which if charged upon your friend, and when the contrary is declared, there should be no fight, for individuals may well differ in their estimated of an individual’s character and standing in society. In case of substitution and a satisfactory arrangement, you are then to inform your friend of all the facts, whose duty it will be to post in person.

- If the party, to whom you present a note, employ a son, father or brother, as a second, you may decline acting with either, on the ground of consanguinity.

- If a minor wishes you to take a note to an adult, decline doing so, on the ground of his minority. But if the adult complained of, had made a companion of the minor in society, you may bear the note.

- When an accommodation is tendered, never require too much; and if the party offering the amende honorable, wishes to give a reason for his conduct in the matter, do not, unless offensive to your friend, refuse to receive it; by so doing you may heal the breach more effectually.

- If a stranger wishes you to bear a note for him, be well satisfied before you do so, that he is on an equality with you; and in presenting the note state to the party the relationship you stand towards him, and what you know and believe about him; for strangers are entitled to redress for wrongs, as well as others, and the rules of honor and hospitality should protect him.

CHAPTER II.

The Party Receiving a Note Before Challenge

- When a note is presented to you by an equal, receive it, and read it, although you may suppose it to be from one you do not intend to meet, which its requisites may be of a character which may readily be complied with. But if the requirements of a note cannot be acceded to, return it, through the medium of your friend, to the person who handed it to you, with your reason for returning it.

- If the note received be in abusive terms, object to its reception, and return it for that reason; but if it be respectful, return an answer of the same character, in which respond correctly and openly to all interrogatories fairly propounded and hand it to your friend, who, it is presumed, you have consulted, and who has advised the answer; direct it to the opposite party, and let it be delivered to his friend.

- You may refuse to receive a note, from a minor, (if you have not made an associate of him); one that has been posted; one that has been publicly disgraced without resenting it; one whose occupation is unlawful; a man in his dotage and a lunatic. There may be other cases, but the character of those enumerated will lead to a correct decision upon those omitted.

If you receive a note from a stranger, you have a right to a reasonable time to ascertain his standing in society, unless he is fully couched for by his friend. - If a party delays calling on you for a week or more, after the supposed insult, and assigns no cause for the delay, if you require it, you may double the time before you respond to him; for the wrong cannot be considered aggravated; if borne patiently for some days, and the time may have been used in preparation and practice.

Second’s Duty of the Party Receiving a Note Before Challenge Sent.

- When consulted by your friend who has received a note requiring explanation, inform him distinctly that he must be governed wholly by you in the progress of the dispute. If he refuses, decline to act on that ground.

- Use your utmost efforts to allay all excitement which your principal may labor under; search diligently into the origin of the misunderstanding; for gentlemen seldom insult each other, unless they labor under some misapprehension or mistake; and when you have discovered the original ground of error, follow each movement to the time of sending the note, and harmony will be restored.

- When your principal refuses to do what you require of him, decline further acting on that ground, and inform the opposing second of your withdrawal from the negotiation.

CHAPTER III

Duty of Challenge and His Second Before Fighting

- After all efforts for a reconciliation are over, the party aggrieved sends a challenge to his adversary, which is delivered to his second.

- Upon the acceptance of the challenge, the seconds make the necessary arrangements for the meeting, in which each party is entitled to a perfect equality. The old notion that the party challenged, was authorized to name the time, place, distance and weapon, has been long since exploded; nor would a man of chivalric honor use such a right, if he possessed it. The time must be soon as practicable, the place such as had ordinarily been used where the parties are, the distance usual, and the weapons that which is most generally used, which, in this Sate, is the pistol.

- If the challengee insist upon what is not usual in time, place, distance and weapon, do not yield the point, and tender in writing what is usual in each, and if her refuses to give satisfaction, then your friend may post him.

- If your friend be determined to fight and not post, you have the right to withdraw. But if you continue to act, and have the right to tender a still more deadly distance and weapon, and he must accept.

- The usual distance is from ten to twenty paces, as may be agreed on; and the seconds in measuring the ground, usually step three feet.

- After all the arrangements are made, the seconds determine the giving of the word and position, by lot; and he who gains has the choice of one or the other, selects whether it be the word or the position, but he cannot have both.

CHAPTER IV.

Duty of Challengee and Second After Challenge Sent.

- The challenge has no option when negotiation has ceased, but the accept the challenge.

- The second makes the necessary arrangements with the second of the person challenging. The arrangements are detailed in the preceding chapter.

CHAPTER V.

Duty of Principals and Seconds on the Ground.

- The principals are to be respectful in meeting, and neither by look or expression irritate each other. They are to be wholly passive, being entirely under the guidance of their seconds.

- When once posted, they are not to quit their positions under any circumstances, without leave or direction of their seconds.

- When the principals are posted, the second giving the word, must tell them to stand firm until he repeats the giving of the word, in the manner it will be given when the parties are at liberty to fire.

- Each second has a loaded pistol, in order to enforce a fair combat according to the rules agreed on; and if a principal fires before the word or time agreed on, he is at liberty to fire at him, and if such second’s principal fall, it is his duty to do so.

- If after a fire, either party be touched, the duel is to end; and no second is excusable who permits a wounded friend to fight; and no second who knows his duty, will permit his friend to fight a man already hit. I am aware there have been many instances where a contest has continued, not only after slight but severe wounds, had been received. In all such cases, I think the seconds are blameable.

- If after an exchange of shots, neither party be hit, it is the duty of the second of the challengee, to approach the second of the challenger and say: “Our friends have exchanged shots, are you satisfied, or is there any cause why the contest should be continued?” If the meeting be of no serious cause of complaint, where the party complaining had in no way been deeply injured, or grossly insulted, the second of the party challenging should reply: “The point of honor being settled, there can, I can conceive, be no objection to a reconciliation, and I propose that our principals meet on middle ground, shake hands and be friends.” If this acceded to by the second of the challengee, the second of the party challenging, says: “We have agreed that the present duel shall cease, the honor of each of you is preserved, and you will meet on middle ground, shake hands and be reconciled.”

- If the insult be of a serious character, it will be the duty of the second of the challenger, to say, in reply to the second of the challengee: “We have been deeply wronged, and if you are not disposed to repair the injury, the contest must continue.” And if the challangee offers nothing by way of reparation, the fight continues until one or the other of the principals is hit.

- If in the case where the contest is ended by the seconds, as mentioned in the sixth rule of this chapter, the parties refuse to meet and be reconciled, it is the duty of the seconds to withdraw from the field, informing their principals, that the contest must be continued under the superintendence of other friends. But if one agrees to this arrangement of the seconds, and the other does not, the second of the disagreeing principal only withdraws.

- If either principal on the ground refuses to fight or continue the fight when required, it is the duty of his second to say to the other second: “I have come upon the ground with a coward, and do tender my apology for an ignorance of his character; you are at liberty to post him.” The second, by such conduct, stands excused to the opposite party.

- When the duel is ended by a party being hit, it is the duty of the second to the party so hit, to announce the fact to the second of the party hitting, who will forthwith tender any assistance he can command to the disabled principal. If the party challenging, hit the challengee, it is his duty to say he is satisfied, and will leave the ground. If the challenger be hit, upon the challengee being informed of it, he should ask through his second whether he is at liberty to leave the ground, which should be asserted to.

CHAPTER VI.

Who Should Be on the Ground

- The principals, seconds, one surgeon and one assistant surgeon to each principal; but the assistant surgeon may be dispensed with.

- Any number of friends that the seconds agree on, may be present, provided they do not come within the degrees of consanguinity mentioned in the seventh rule of Chapter I.

- Persons admitted on the ground, are carefully to abstain by word or behavior, from any act that might be the least exceptionable; nor should they stand near the principals or seconds, or hold conversations with them.

CHAPTER VII

Arms, and Manner of Loading and Presenting Them.

- The arms used should be smooth-bore pistols, not exceeding nine inches in length, with flint and steel. Percussion pistols may be mutually used if agteed on, but to object on that account is lawful.

- Each second informs the other when he is about to load, and invites his presence, but the seconds rarely attend on such invitation, as gentlemen may be safely trusted in the matter.

- The second, in presenting the pistol to his friend, should never put it in his pistol hand, but should place it in the other, which is grasped midway the barrel, with muzzle pointing in the contrary way to that which he is to fire, informing him that his pistol is loaded and ready for use. Before the word is given, the principal grasps the butt firmly in his pistol hand, and brings it round, with the muzzle downward, to the fighting position.

- The fighting position, is with the muzzle down and the barrel from you; for although it may be agreed that you may hold your pistol with the muzzle up, it may be objected to, as you can fire sooner from that position, and consequently have a decided advantage, which ought not to be claimed, and should not be granted.

CHAPTER VIII.

The Degree of Insult, and How Compromised

- The prevailing rule is, that words used in retort, although more violent and disrespectful than those first used, will not satisfy, – words being no satisfaction for words.

- When words are used, and a blow given in return, the insult is avenged; and if redress be sought, it must be from the person receiving the blow.

- When blows are given in the first instance and not returned, and the person first striking, be badly beaten or otherwise, the party first struck is to make the demand, for blows do not satisfy a blow.

- Insults at a wine table, when the company are over-excited, must be answered for; and if the party insulting have no recollection of the insult, it is his duty to say so in writing, and negative the insult. For instance, if a man say: “you are a liar and no gentleman,” he must, in addition to the plea of want of recollection, say: “I believe the party insulted to be a man of the strictest veracity and a gentleman.”

- Intoxication is not a full excuse for insult, but it will greatly palliate. If it was a full excuse, it might be well counterfeited to wound feelings, or destroy character.

- In all cases of intoxication, the seconds must use a sound discretion under the above general rules.

- Can every insult be compromised? Is a mooted and vexed question. On this subject, no rules can be given that will be satisfactory. The old opinion, that a blow must require blood, is not of force. Blows may be compromised in many cases. What those are, much depend on the seconds.

Some highlights from the Appendix.

Rule 12. In simple unpremeditated rencontres with the small sword or cou-teau-de-chasse, the rule is, first draw, first sheathe; unless blood be drawn: then both sheathe, and proceed to investigation.

Rule 14. Seconds to be of equal rank in society with the principals they attend, inasmuch as a second may choose or chance to become a principal, and equality is indispensable.

Rule 15. Challenges are never to be delivered at night, unless the party to be challenged intend leaving the place of offence before morning; for it is desirable to avoid all hot-headed proceedings.

Rule 17. The challenged chooses his ground; the challenger chooses his distance; the seconds fix the time and terms of firing.

Rule 20. In all cases a miss-fire is equivalent to a shot, and a snap or non-cock is to be considered as a miss-fire.

Rule 25. When seconds disagree, and resolve to exchange shots themselves, it must be at the same time and at right angles with their principals.

* All drawings from “DUELLING in OLD New Orleans,” by Stuart O. Landry. Harmanson, Publisher. 1950.