A few weeks ago, I had the pleasure of walking around St. Louis No. 3 with the lovely Poppy Tooker to talk about the cemetery for her fabulous radio show Louisiana Eats. Poppy’s love of New Orleans extends outside of the kitchen and her passionate and vibrant personality is apparent in everything she does.

On our stroll, we talked about a variety of subjects, but one of the main topics we discussed was All Saints’ Day.

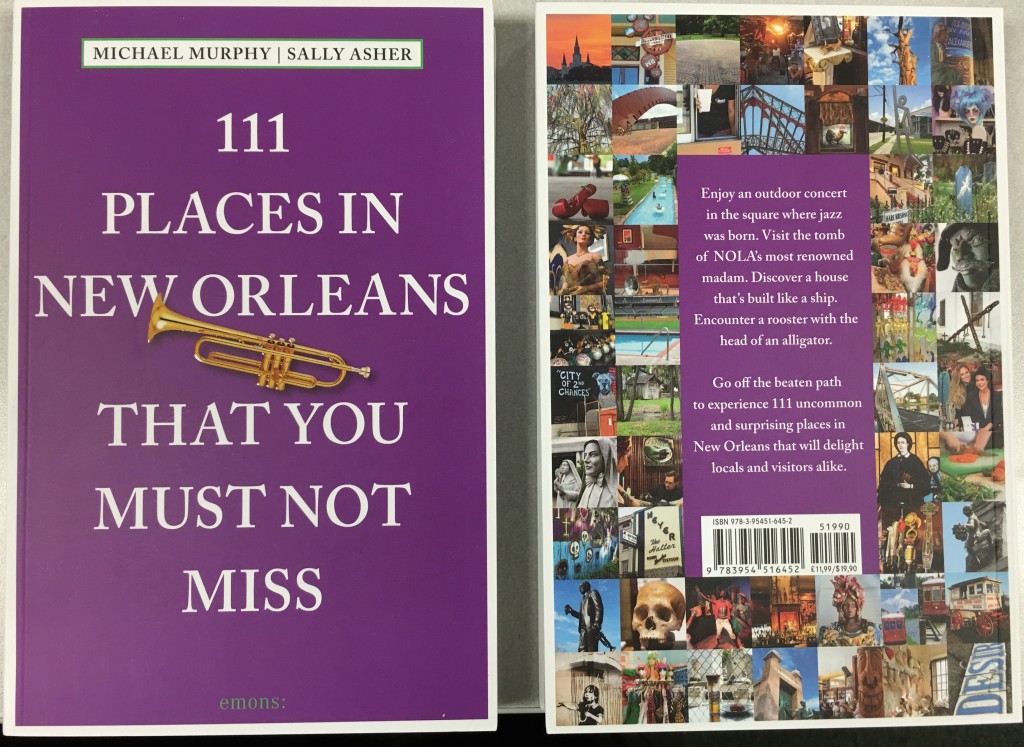

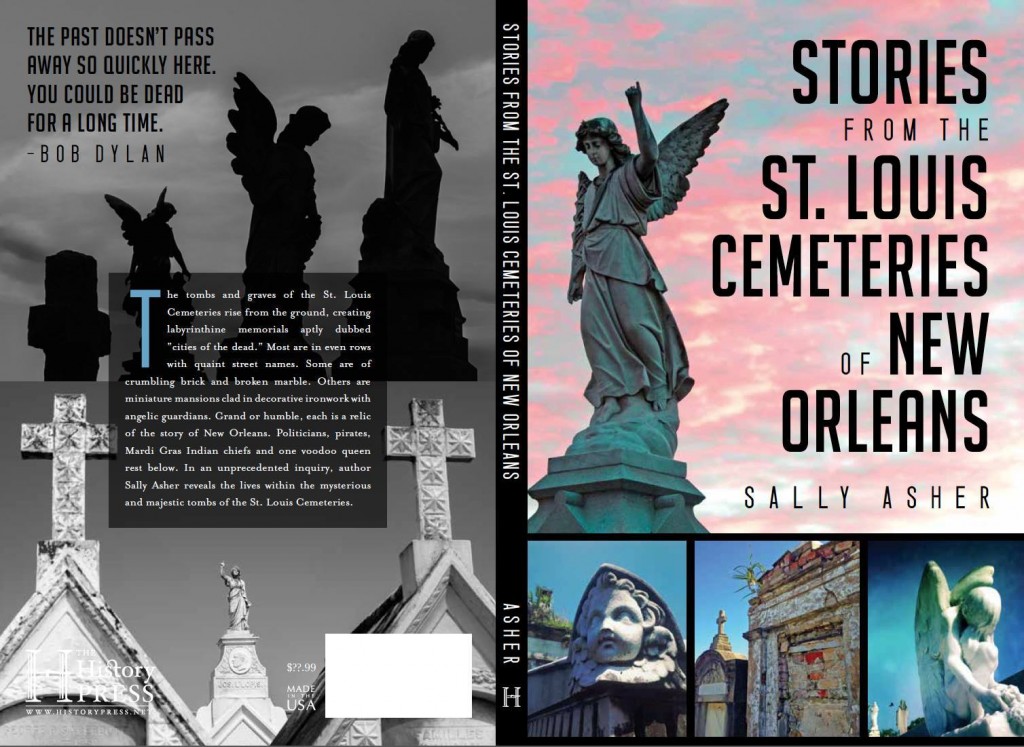

I discuss All Saints’ Day in my new book Stories from the St. Louis Cemeteries of New Orleans, but of course I never really have enough room to write about EVERYTHING (word count is always an issue for me). So in honor of All Saints’ Day, here are a few extra things about the holiday.

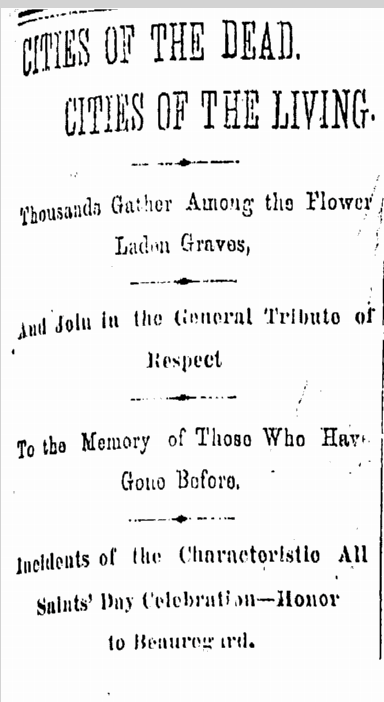

Headline from 1894.

It was also known as La Toussaint. French Creoles called it that, a term that was common until almost the middle of the twentieth century.

An ad in French and English from 1866.

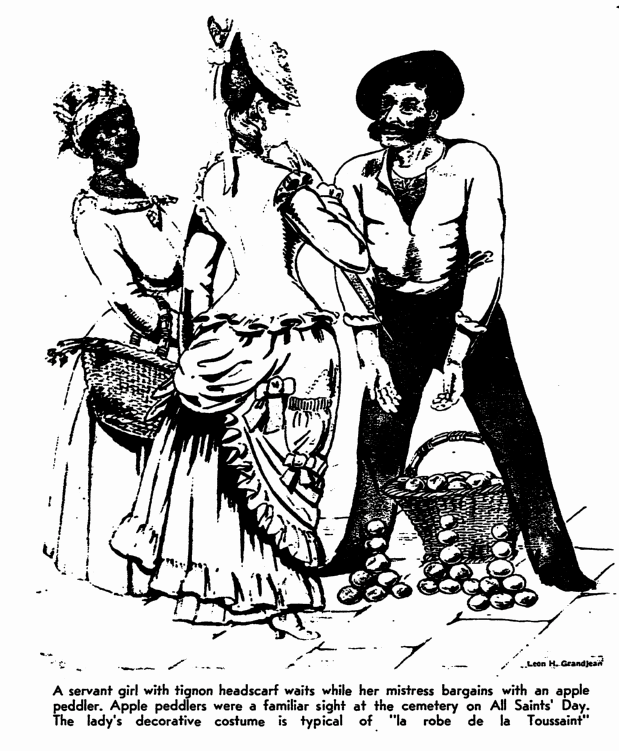

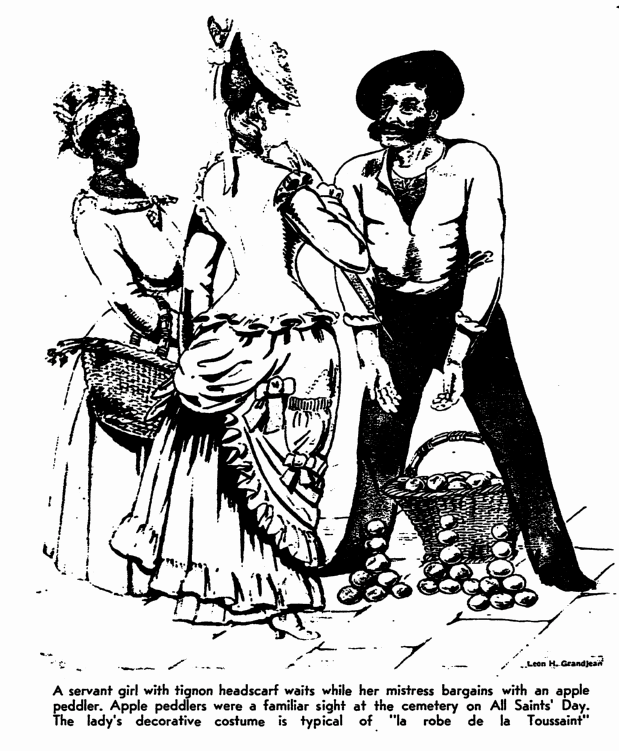

It was a fashion show. It was the first day when “La robe de la Toussaint” was worn by women and children. They wore dark clothes made in the finest materials they could afford. The Times-Picayune wrote about in 1951. “With the cemeteries serving as open-air style shows, the same festive air prevailed which nowadays is reserved for Easter Sunday.”

A photograph from 1951.

New Orleans encouraged visitors and non-Catholics to take part.

We reiterate the invitation we yesterday gave to strangers to visit the Catholic Cemetery to-day [St. Louis No. 1]; and as it may be interesting to some of our readers, we shall here publish some observations that we inserted in our private scrap book a year or two since.

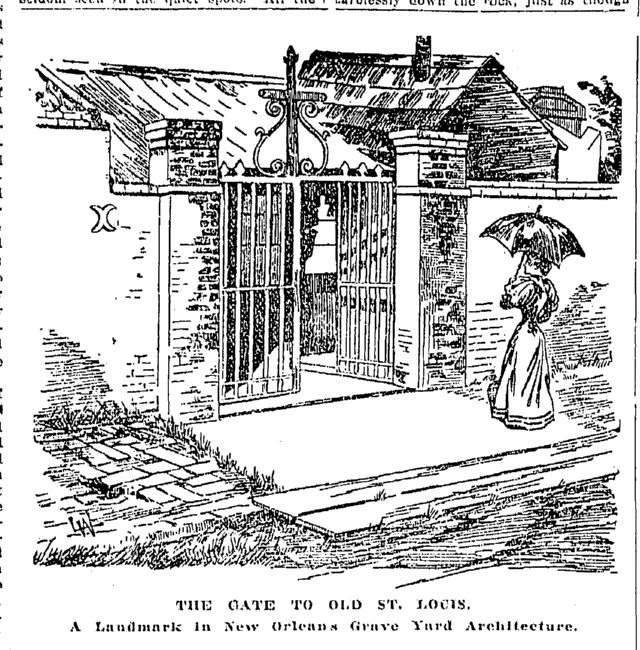

To a stranger, there are few objects more striking than the mode of interment practiced in this city. Actual inhumation is rarely seen. When it is attempted, the ground is sometimes so saturated with water, that the most revolting scenes are connected with the last sad duties which the living performs for his departed comrade. Hence the customary manner of burial is to deposit the corpse in a tomb raised above the surface of the ground.

The Catholic Cemetery is a fine illustration. At the same time, it constitutes a diversified monument, not only of the virtues of the dead, but the classic taste of the living. In its very appearance, it is a “City of the Dead.” Its streets, intersecting each other at right angles; the neat little edifices constructed for the last home of humanity; here and there overtopping its neighbors, and glittering with the rich gildings of the crucifix or with some magnificent escutcheon; the splendid railing which encloses some of these mansions, and the willow trees, scattered over the ground; all these together with the surrounding wall, unite in impressing one with the idea of a miniature city.

The handsome shelled pavements, the neatness even of the most humble tombs, and the great variety of pursuit and of nativity, as indicated by the epitaphs, renders this cemetery an attractive resort at any time. Here you may walk for hours, sympathizing with Hervey [James Hervey] in all the florid beauty of his “Meditations” [“Meditations Among the Tombs”]; and in a thousand circumstances, you can find even richer themes for reflection than those suggested to his mind.

All Saints Day (Nov. 1), is observed at this place with great éclat. It is several years since we first beheld the scenes usual on this festival. Never shall we forget them. The thought that then, fifteen, or twenty thousand people, leaving their occupations to spend a day in company with the remains of beloved associates or relatives – to cherish the remembrance of their virtues, and to decorate their tombs with garlands and evergreens – presented before us the affections of the human heart in an aspect they had never assumed before. It was a species of beauty of which we had indeed heard – we had read of it in the pages of inspiration, and in the philosophy of heathen sages; but never had out perceptions grasped even the outline. It was reserved for the simple, the unostentatious, the affecting incidents of All Saints Day, to delineate, in brilliant colors, the features of a great truth as eminent for its beauty as it is important in its relations. – The Daily Picayune. November 1, 1838.

An article from 1842.

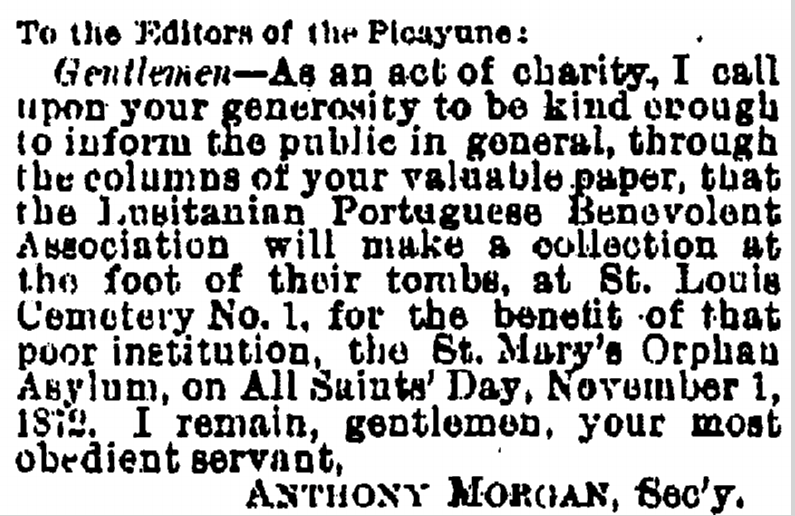

It was a time to take collections up for orphanages. Typically, orphans were dressed up and trotted out to stand in front of the gates. Nuns and orphans were positioned at almost every gate holding wooden plates for visitors to drop money into. Sometimes the children rang a bell or beat the plate with a stick to attract attention. Benevolent Society Tombs also took offerings usually for specific orphanages. They would borrow an orphan or two to stand by their tombs for greater effect.

Letter to the editor from 1872.

It was a popular time for peddlers and vendors who set up outside of the cemetery gates. “L’estomac mulatte,” a flat ginger cake dented on the sides and sometimes covered with white or pink icing was a popular treat – so were pecan pralines, “calas,” a rice cake, apples, popcorn, and candy. Balloons and toy skeletons on strings were sold. Florists were booming as were saloons where men usually retreated to enjoy “La Biere Creole,” a Creole beer made from the juice and pulp of pineapple.

Killing a lizard was hazardous. Children were warned not to kill lizards in a cemetery or they would be dead in a year. According to the superstition if they did it on All Saints’ Day it would bring their end much quicker.

Killing a lizard was hazardous. Children were warned not to kill lizards in a cemetery or they would be dead in a year. According to the superstition if they did it on All Saints’ Day it would bring their end much quicker.

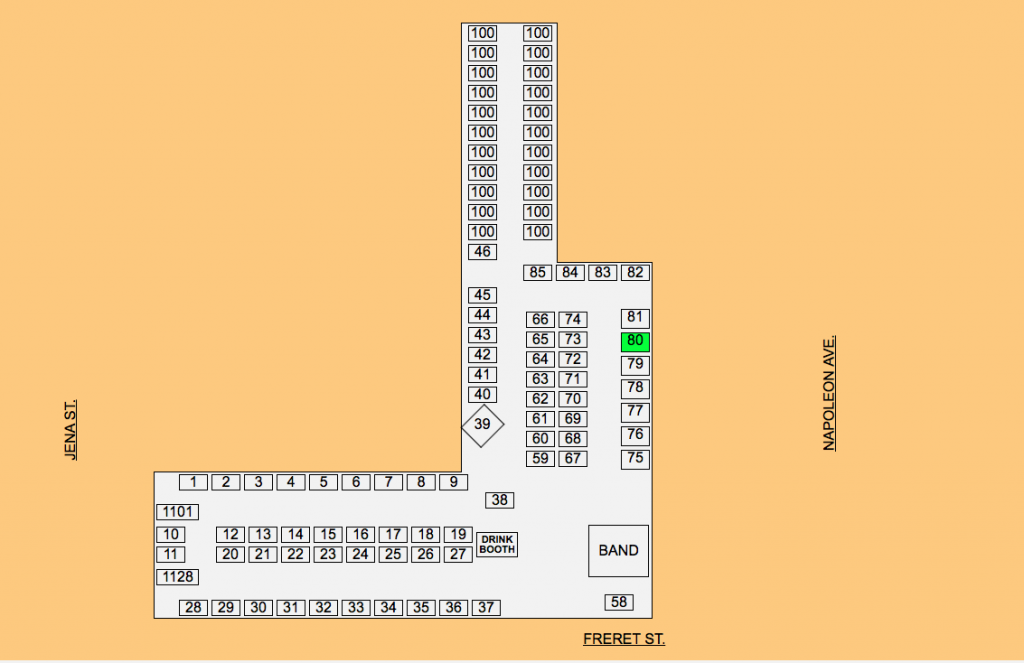

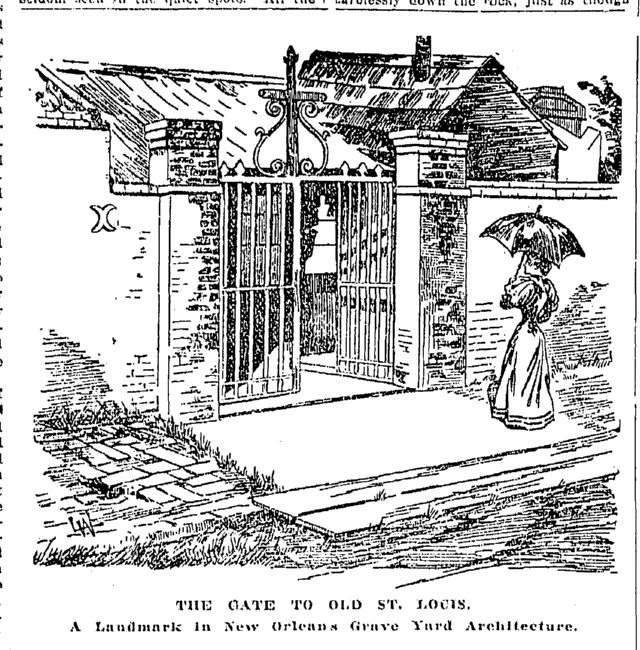

An illustration from 1894.

You can hear my interview with Poppy Tooker HERE.

Poppy and I standing in front of Jean Galatoire’s grave.

Enjoy and Happy All Saints’ Day!